Cutting WEDGE

With looks as sharp as a shard of glass, the Lotus

Esprit S1 has always

been a flamboyant machine — but has it the performance to match?

Where better than Monte Carlo of find out...

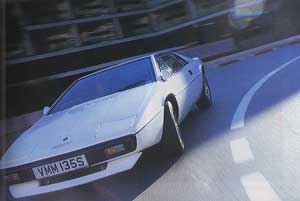

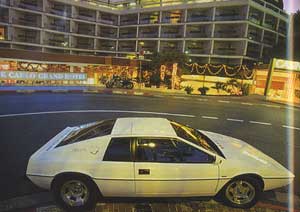

Go on, admit it: whenever you think of the original Lotus Esprit, you think sleek bodywork as flawlessly white as Ursula Andress's bikini, Wolfrace alloys glinting in the Mediterranean twilight, the tortuous challenge of a deserted coast road, handsome texedoed strangers in glitzy casinos ordering Vodka Martinis — shaken, not stirred — and the car's uncanny ability to sprout submarine fins and shoot down helicopters with its concealed rockect launcher.

In other words, the Lotus Esprit S1 is inextricably linked to the James Bond legend, thanks chiefly to its starring role alongside an irrepressibly cool Roger Moore in the 1977 movie The Spy Who Loved Me. Few who have seen the famous helicopter chase scene can shake from their memory the vision of the Esprit outrunning the aircraft on a winding road before transforming miraculously from sports car to submersible. It's the reason why the Esprit S1 is so well remembered; the reason why Nick Pope — owner of the car in our pictures — insisted on white when he restored his car; the reason we injected an apt Mediterranean air to our story by photographing the Esprit in Monte Carlo; the reason why new Esprits still sell healthily today.

But to suggest that the Esprit S1 is nothing more than a posing pouch for wannabe Bonds is to do it the cruellest of disservices. It's a Lotus, after all, so you can take it as gospel that the Esprit handles better than all its rivals and as well as any driver has a right to expect. It's brisk too, thanks to the 160bhp pumped out by its state-of-the-art 16-valve four-cylinder engine, but not quite so brisk as its beautifully simplistic Giugiaro-designed wedge styling would have you believe. But however marvellously the Esprit drives, it's for that alluring shape that it's best remembered. After all it was the sleek 'folded paper' look that convinced Bond producer Cubby Broccoli to use the car in The Spy Who Loved Me. Lotus well understood the value of placing their carss in films following the huge interest in Sevenss generated by cult drama The Prisoner, and tried to instil a certain 'star quality' in all of their products. According to popular legend, Lotus sealed the Bond contract by parking a pre-production Esprit outside Pinewood studios and letting the car's styling sell itself.

AS YOUR EYES glide acrosss the angular fluency of the Esprit's bodywork, it's easy to forget that the first design study was penned as early at 1972 for the Turin show as a possible replacement for the mid-engined Europa. The glorious body, which initially featured frontal air fins and a one-piece tilting rear section, shrouded nothing more than a crudely widened and lengthened Europa chassis. Little thought was given to the transmission layout beyond incorporating the new Lotus 907 engine as used in the Jensen-Healey. Because of its long-nose styling, which Giugiaro so favoured in the Seventies, the Italian at first wanted to call the car 'Kiwi'. Lotus, on the other hand, intended to continue the 'E' that began with the Eleven. The 'Esprit' moniker arose not from some flash of inspiration in the Lotus boardroom, but a weekend with a dictionary, which somehow typifies the company's amsuingly phlegmatic attitude to its products. Even headstrong Giugiaro came round to the Lotus way of thinking when it was pointed out that in England the 'Kiwi' moniker is synonymous with a well-known brand of boot polish.

Initial reaction to the car in Turin was positive enough for Lotus to proceed with development. Lotus founder Colin Chapman initially hoped that the car would be in production within 18 months, but in true Lotus fashion it took rather longer than that to convert a handsome shape into a workable product.

Mechanically, there was little on the Esprit to surprise the seasoned Lotus lover. Once more the company from Hethel, Norfolk employed their familiar steel backbone chassis to support Giugiaro's glassfibre body, this time using a crossmember for the essentially Opel Ascona front suspension and a fork at the rear of the chassis that accommodated Lotus' 907 engine mounted amidships at 45 degrees and distinctive rear suspension. The rear suspension comprised lower transverse links and box-section semi-trailing arms, plus fixed-length driveshafts that doubled as the upper suspension links, combined coil spring/damper units and inboard rear brakes. Getting this system to work (and funding its development) was one of the stumbling blocks in the Esprit's gestation period, but it was the new 907 engine that caused the biggest headaches.

Lotus had been trying to produce its own engine since the mid-sixties, when Ford announced it intended to stop making the blocks used for Lotus' twin-cam engines. But the cost of tooling up for a new engine was too much for Lotus to stand alone. When a deal with Jensen was struck, it must have seemed like the perfect solution: Jensen would contribute to development costs, and in return would be first to use the new engine in their Jensen-Healey sports car.

The scheme might have worked — had the two companies been less similar in their approach to planning and organisation. Owing to a series of management reshuffles and disasters, Jensen left the decision on which engine to use in the Jensen-Healey imposssibly late, and consequently needed large numbers of engines before Lotus could supply any. The first batch of engines delieved to Jensen bore signs of a decidedly rushed job. While meeting Lotus' targets on weight (just 275lb complete) and power (140bhp), the units suffered distortion of their iron liners, heavy oil consumption and oil circulation problems during cold starts and at high revs.

Matters were further hampered by the infamous power cuts of the early Seventies, which wreaked havoc on Lotus' delicate new engine tooling. It took until the end of 1974 for Lotus to catch up sufficiently on engine production (chiefly because the Jensen-Healey's bad reputation had led to disappointing sales) and properly address reliability. This coincided with — at last — the launch of Lotus's first 907-engined car, the Elite, and a fully working Esprit prototype.

It seems extraordinary that Lotus managed to progress the Esprit at all inbetween sorting the 907 engine, preparing the Elite for production and winning the Grand Prix world championship. But progress it they did, with Chapman, design engineer Michael Kimberley and design chief Oliver Winterbottom flying to Italy once or twice a week in a rickety light aircraft to work with Giugiaro on the practicalities of the styling, such as lessening the rake of the window by 2 degrees to meet visibility legislation. In Lotus Esprit: The Complete Story by Jeremy Walton, Kimberley remembers:

'We had some epic flights to and fro, including one occasion where the plane did not have enough oxygen and had to fly between the Alps to keep the occupants conscious. Then we landed, feeling a bit sleepy, and still had a full day of design development to do. But it was great to see Colin and Giugiaro spark off each other to get the windscreen right.'

Developing the Esprit's mechanics fell to former Rolls-Royce and BRM engineer Tony Rudd. Once Rudd had improved the engine frailties exposed by the Jensen-Healey, his biggest challenges were to find a suitable means of transmission for the Esprit and couple this with Lotus' own rear suspension design. The answer lay conveniently in the five-speed transaxle of the exotic but ultimately ill-fated Maserati-engined Citroen SM, which had to be make to work with a new engine in the 'wrong' end of the car. Lotus negotiated the machining of their chosen gear ratios on Citroen tooling, but expected to design their own crownwheel and pinion to reverse the direction of wheel rotation. They got very close to their produciton deadline before someone discovered that the Citroen engine ran backwards and the original set-up would be fine...

Although Chapman didn't work directly on the Esprit's mechanics, he oversaw the proceedings in his own inimitable way, checking costs and weight-saving on the inboard rear brakes and rear suspension in particular. When stress tests showed that a cross-bolted strengthening channel would be needed between the suspension link inner mountings, Chapman was adamant that it would be fine without and demanded it be removed. Shortly after, Rudd took the first completed Esprit to meet the 'Old Man' at Heathrow airport on his return from the 1975 Argentinian GP. A delighted Chapman jumped in the raced off on his first drive, which ended in a shower of sparks after only a few hundred yards with the spectacular collapse of the rear suspension. On climbing from the wreckage, Chapman simply left mechanics to sweep up the debris while he continued his journey in a back-up Elite, muttering 'That'll teach me to keep my mouth shut'.

THE LONG-AWAITED public launch of the Esprit at the 1975 Paris motor show represented an important change of direction for Lotus. The new car continued Lotus' climb away from its kit-car roots and took the Norfolk company closer than ever before to the upper echelons of Porsche, Ferrari and Maserati. On paper and on the show stand, it looked every inch the sure-fire winner that would save Lotus from falling victim to the endemic oil crisis-inspired drop in car sales. Its fuss-free wadge styling was as much a technical tour de force as a magnet for style-conscious customers — a drag coefficient of 0.34Cd was impressive for the Seventies, especially as there were enormous wheels and tyres to shield and the problem of feeding the mid-mounted engine with enough air to keep it cool. In fact, the only major addition to Giugiaro's original slippery shape was a spoiler below the front bumper to keep the front end pressed onto the road at Lotus' claimed top speed of 138mph. Even the price — approimatley £4500 including all taxes, said Lotus in Paris — seemed too good to be true for a small-engined supercar.

It was. Once launch fever had passed, Lotus revised list price to £5844, and as cars finally became available to press and public early in 1976 a realistic on-road price for a high-specification car was close to the £8000 mark. Equally, independent testing suggested that the claimed top speed of 138mph was more than 10mph too high, and the quoted 0-60mph of seven seconds around a second too low. While this may have been slightly disappointing for a car whose go-faster styling promised so much, customers took greater umbrage at the engine's chronic overheating problems due to the insubstantial nose-mounted radiator and weak engine-bay air circulation (from and S2, all Esprits use 'elephant ear' vents to feed cool air to the engine bay), plus poor aperture seals that let in water and fumes and a litany of electrical problems, from failing fuel pumps to a poorly-located coil that overheated and pop-up headlamps that refused to retract at three-figure speeds (which was cured by fitting a second electric motor). Lotus even experimented with an avante-garde self-colouring dye system for the Esprit's GRP panels in 1977. They quickly attained smooth finishes to rival conventional painting, but colour match problems between the shell and auxiliary panels spelt the end of this technique in a matter of months.

Despite its many failings, the Esprit S1's exceptional looks and handling ensured in became a strong enough seller in less than three years to guaranteee the future of the Esprit name through a series of improved incarnationss. But as later cars became infinitely faster and better constructed, so the original S1 with all its foibles became old hat, frowned upon and ridiculed by those whose only interest lie in the latest and greatest state-of-the-art sports cars.

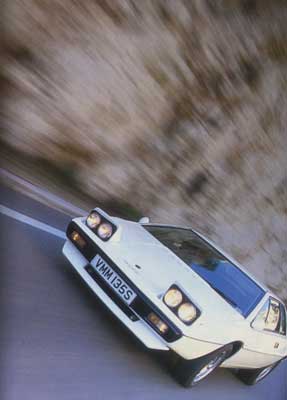

Fortunately, time has mellowed the criticisms of the Esprit and enthusiasts are once more beginning to appreciate its unique artistry, which kick-started Lotus' success since the Seventies. With its failings well documented and virtually eradicated by dediated specialists, the S1's time has arrived once more — and nothing brings this home more readily than being confronted by the so-familiar yet sadly rare sight of a pristine white Esprit S1 glinting in the winter sun beside Monte Carlo harbour. In a town where out -of-the-ordinary is the norm, people stop and stare, then sidle over to drink in the purity of a car they'd forgotten was so striking. Only when you see an S1 in the glassfibre does it hit you how little justice the real car is done by all those hackneyed images of the Bondmobile that have been bombarding your retinas all these yearss. When was the last time you were able to scan along that slender arrowed nose to a stocky chock of monocoque completely deviod of unsightly spoilers, air intakes and other lashed-on ephemera that Giugiaro had the decency to refrain from using on his first draft? When were you last able to pace around one, marvelling at how wide and low-slung its 44-inch high body looks, smiling quietly to yourself as the kitsch chrome Wolfrace alloys catch the light like an impish grin in a burlesque comedy film? When were you last able to hook your thumb behind the flap-happy Morris Marina doorhandle and slip deep into the body-hugging bucket seat?

In a concession to common decency, this car's original tartan cloth upholstery has been replaced by acres of sumptuous black leathercloth. It contrasts with the white paint and suits the car well, quickly stifling the squeak of protest that its splendour has been reduced from the part of you that is amused by Noddy Holder's sideburns and corduroy safari jackets with elbow patches. Once you've untangled your (thankfully unflared) trouser leg from the stumpy handbrake lever that's placed on the outer sill exactly where you get in, it's a relief to discover that, for once, this is a Lotus that affords ample room to those who are more amply proportioned than the average racing driver. The pedals are canted to the left far down a spacious footwell, and with dainty shoes my size 10s could flit between the controls without mishap. This unexpected comfort is usually attributed to 6ft 5in Lotus design engineer Mke Kimberley, who made sure he'd be able to squeeze into the car he'd spent four years developing.

Dominating the dash in front of me is a huge cresent-shape instrument binnacle, which houses green-tinted Veglia analogue dials deep within it to virtually eliminate glare onto the steeply-raked windscreen. The three-pronged steering wheel (a welcome replacement on this car from the ugly two-pronged affair found on the first S1s) is an arm's length away, meaning you have to sit in a slightly knees-up position to feel comfortable. The view through the screen is fantastic except for the chunky door pillar that slant straight into your line of vision when you take all but the shollwest of corners. And to the rear? The dinky circular door mirrors offer a much finer view of the rear bodywork than of following traffic until yu cant your head, and the Esprit is as guilty as most mid-engined cars of the dreaded rear three-quarter blind spot unless you make sure to stop 90 degress to the give way line.

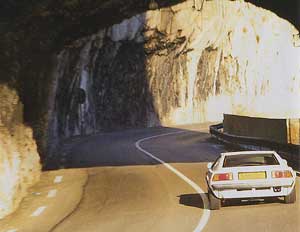

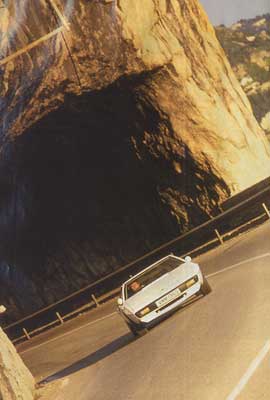

When you flick the well-hidden ignition key on the steering column beneath the instrument crescent, the coarse loingitudinally-mounted 16-valve engine adds itself instandly to the list of S1 plus points. It idles gruffly, especially when cold, but pricks up with a snarl the moment you think about touching the throttle. As you ease up the light clutch, the engine is reluctant to get things moving unless you use 2000rpm, owing to a combination of peaky cams for top-end power and a tall first gear. This makes for clumsy progresss through the stop-start traffic bunging up Monte Carlo's narrow streets, but once you've picked your way through the principality's labyrinth of rock-hewn tunnels and concealed bolt-holes, the Lotus gets quickly into its stride. A 6200rpm red-line means you can use all the 160bhp in the long first gear before notching the dainty little gearlever atop the transmission into the second of its five ratios. After much criticism of the old Europa's gearchange, it's great that the effort Lotus put into perfecting the Esprit's rod-and-cable gear linkage paid off so handsomely — in fack, Tony Rudd once said the Esprit was worth the asking price for the gearchange alone, and you got the rest of the car free! Flicking between closely spaced third and fourth ratios, the Esprit laughs in the face of the twisty coast road to Nice, proving that you don't need the power of a locomotive to get a hurry on around the Cote d'Azur's fabulous roads. Only when you slot the lever far to the right for leggy fifth do you yearn for the power that later Esprits offer. No more will the S1 kick forward like a sprinter and spin its engine saucily up through the revs.

No matter, because the din the S1 makes at a leisurely 80mph on the frequently tunnelled auto-toll in the hills above Monaco gives the impression that you cracked the ton a long while ago. Those grippy tyres roar on the road as loudly as the cammy straight four behind your head, and for sleek a shape the Esprit musters a fine chorus of wind noise. Just in case year ears miss a stray resonance, the backbone chassis transmits every vibration straight to your left hip and elbow, due mainly to the supplementary role of the driveshaft as rear suspension top links, which require extra-hard engine and transaxle mounting bushes to cope with the cornering forces.

But who's complaining? Esprit S1s aren't meant to flounce along the autoroute, so do yourself a favour by popping it down a couple of cogs and heading back to the intoxicating twists that wend you along the magnificant craggy coastline. Suddenly the noise is music, the vibration becomes communication and you become Mario Andretti. Steering that felt clumsy at parking speeds with an impractically large turning circle beomces wonderfully balanced and sensitive, continuing a Lotus tradition that few, if any, can match even today. As the car darts unerringly to the apex of every corner, you have to pinch yourself to belive that the front suspension guiding you have been lifted virtually unchanged from the then-current Opel Ascona. The Lotus maxim of soft springs and taut dampers keeps the ride firm but not rattly and jarring, so you glide a path through the endless rocky outcrops like a yacht on the swell rather than bounce and skit across the road. In the dry, grip is not an issue — the only thing that checks your confidence when cornering fast is the irritating lump of door pillar that stands perpetually between you and a clear view round the bend. Lean the car hard into the turn and it complies with a frugal dose of body roll, but unless the surface is greasy or you've got a death-wish the rear wheels will dutifully follow the fronts. It's strangely conforting to drive an excellent-handling car that isn't inclined to oversteer, and you quickly find yourself striving for impeccable lines and satisfying fluidity of motion rather than playing with the throttle like some trigger-happy rallycrosser. Who wants to be Tiff Needell when you can be Alain Prost?

With the excitement over, a robust squish of the brake pedal stops the car as effectively as a brick wall, thanks again to huge tyres and discs all round. A slight bias to the rear keeps braking a stable affair — provided you're not mid-corner — and prevents premature locking of the light-loaded front wheels. It's only now that you notice the sweat on your brow. The cockpit ventilatess with all the efficiency of a pressure cooker, so that glaring Mediterranean sunlight through the greenhouse-like windscreen and heat soak from the nearby engine leave you succulently sauteed in your own juices. Opening the window is little reprieve, as the clean airflow across the car directs barely a puff of wind inside. But however hot you get, you'll be in better shape than your luggage, two items of which can be stashed in a slim cavity behind the engine. A shopping car it ain't — your groceries would be cooked before you'd left the supermarket car park.

After scrambling out of the Esprit and cursing again the daft handbrake that you scrape your shin on, an irrepressible urge to stand and take stock of it washes over you. A car this majestic was always meant to be admired, but the new-found knowledge that it really does drive as well as it looks further fortifies its purposeful stance. You can understand the misgivings of those in the Seventies who felt that the Esprit S1's driving experience couldn't live up to the looks and price tag, but to maintain such a view now is to misunderstand it. That was then, and this is now; and right now it's hard to imagine another car that wears its spirit so boldly on its sleeve when both standing still and racing along.

|

|